Making Austin's libraries greater

We need libraries more than ever.

Will Council reclaim its Planning Commission appointments? Per the city charter, there are 13 voting members of the Planning Commission. All 11 Council members nominate one member, subject to Council approval. For some reason, it has been accepted in the eight years since the beginning of the 10-1 era that the mayor nominates the remaining two members. There's a certain intuitive logic to it; it's much less complicated than having everyone on Council try to jointly decide on a nomination. But that tradition is a privilege, not a right. Why should Council members accept the mayor taking advantage of that tradition to appoint someone to the commission who doesn't share Council's stated goal of addressing Austin's housing crisis?

Arlington ends single-family zoning: The suburban Virginia county will phase in new zoning rules that will allow developments of 4-6 units on most lots that were previously reserved for single-family homes. This is the most aggressive across-the-board reform I've seen in a traditionally suburban area. The fierce debates about ending SF zoning elsewhere often center on far more modest proposals, such as allowing duplexes or triplexes. It's also worth noting that Arlington's embrace of this type of "missing middle" housing came after it recognized that the old compromise (density on the corridors, single-family in the interior) wasn't good enough.

Austin's libraries: an intrinsic community benefit

Last week City Council adopted the Austin Public Library long-range Strategic Plan, a 118-page document (a lot of photos, but still) that envisions the construction of new facilities and the improvement and expansion of existing ones.

I recall a conversation a couple years ago with a senior city official who still believed the new Central Library was a mistake. In an era of free-flowing information online, libraries were not nearly as important of a resource as they used to be, he reasoned. What unique value does a new library provide to citizens who have plenty of other ways to access books and information?

I vehemently disagreed with his view. Libraries in general, and the new Central Library in particular, strike me as some of the best investments a local government can make.

First, they provide value simply as comfortable, public spaces. They're the indoor, quieter version of parks. Where else can you find an indoor space without having to buy something? There's something for everyone, regardless of age or status.

Second, I don't view the books on the library shelves as a limited, antiquated version of what's available online. On the contrary, I view them as a valuable refuge from the profit-driven information economy that has captured our attention at tremendous cost to our mental wellbeing. Libraries offer you the chance to actually seek information and entertainment freely, unencumbered by algorithms that feed you a steady diet of shallow distractions, leaving you exhausted and unfulfilled.

The city spent much more time and money building the new Central Library than planned. It was held up by critics as a symbol of government profligacy and incompetence. It has been a ringing success though. About three times as many people (100,000) visit the central library each month than visited the old Faulk Library on Guadalupe.

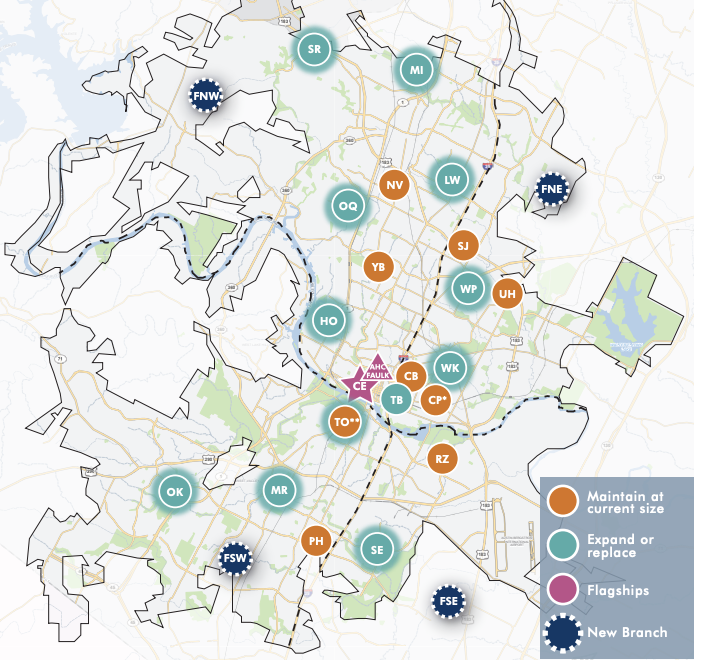

The map below shows our existing libraries as well as four proposed new branches. Their location, on the edges of the city, align with where our population growth has occurred.

More than half of the existing branches are designated for future expansion, with the goal of making them at least 30,000 square feet. In some cases that will come through an addition or renovation, while in others it could mean relocation. For instance, the Menchaca Road branch, the site nearest to me, is currently 14,500 square feet and is proposed to eventually more than double in size, either through expansion or replacement. The only two branches that are larger are George Washington Carver (15,000 sq ft) and Daniel E. Ruiz (16,000). Other branches are much smaller, such as Cepeda (8,000 sq ft), Old Quarry (8,300), Pleasant Hill (9,500).

So doubling or tripling the size of many of these branches is a pretty ambitious undertaking. The money is not currently available; voters will need to approve a bond package to fund the projects. Past bonds to improve libraries –– one as recently as 2018 –– have passed easily and I believe they'll continue to pass.

The real financial challenge comes from staffing, which cannot be funded through voter-approved bond dollars. Do bigger branches necessarily require more full-time staff? I don't know, but they will certainly require more maintenance, which requires staff.

As is always the case when we talk about staffing challenges, I will remind you that the city of Austin is operating under unsustainable state-imposed revenue constraints. In the coming years, the city will either have to substantially cut services or ask voters to approve a significant tax rate increase. The 3.5% per-year increase that is allowed without voter approval is simply not enough to keep the lights on long-term!

What is an intrinsic benefit?

I describe the libraries as intrinsically beneficial because they don't need to be justified in economic terms. Sure, there probably is an economic benefit, and certainly the construction project provides an economic stimulus, but that's not the point. That stands in sharp contrast to, say, a Convention Center, which provides little value outside of the purported economic gains.