What is Austin doing about flooding?

What about next time?

The horror show unleashed on Central Texas over the weekend is yet another urgent reminder from Mother Nature for the city of Austin to prepare for an era of extreme weather events.

There are lessons to be learned from every disaster, but we also have a tendency to prepare for the next disaster as if it will be exactly like the one that just occurred. After Uri, the focus was on warming shelters. After Mara, it was protecting power lines from falling trees. In the wake of the unspeakable tragedy wrought by the weekend floods, there will likely be calls for increased investment in flood mitigation. That is not unjustified, but ideally this will motivate increased vigilance around other types of disasters that are not as fresh in our collective memory. For instance, wildfires. Imagine a wildfire that is 10x as bad as the one that swept through Steiner Ranch 14 years ago. In other words, what California faced earlier year.

Today, however, I want to take a look at what the city has done on flooding in recent years. In the coming days, I hope to gather more information and talk to city officials about what more can be done in the future, both on flooding and other disasters.

What if the worst rains had hit Austin?

I asked the Watershed Protection Department what they would expect to happen if the heaviest rains that fell in Texas over the July 4th weekend had fallen on Austin. Here is what Karl McArthur, a Supervising Engineer in the WPD's Modeling & Floodplain Office said:

If either the rainfall that fell in the Kerrville area or in the area to the north of Lake Travis and into the San Gabriel River basin were to fall on Austin we would have significant flooding issues. The rainfall from these events was similar in character to the rainfall from the October 30, 2015 and May 26, 2016 flood events that so significantly impacted southeast Austin. The rainfall from the July 4/5 event was similar in intensity to these events but spread over a considerably larger area, so we would expect wide-spread flooding issue across a significant portion of the City.

The Memorial Day 1981 flood is probably most similar to what would have happened if the event had occurred over the urban core north of the river. That said, the rainfall amounts and extent of the July 4/5 events was greater than this historic flood event. We are better prepared for such flooding now than we were back in 1981 because of a number of projects and a tightening of regulations related to development in the floodplain, but an event like this would cause problems no matter where in Austin it fell.

Atlas 14: the rainfall study that redefined Austin's floodplains

In 2018, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration published a study on rainfall in Texas –– dubbed "Atlas 14" –– that dramatically altered assumptions about flooding risk throughout the state.

In Austin, Atlas 14 found that what had long considered a 500-year rainfall event (13.5 inches in 24 hours) was actually closer to a 100-year event. In other words, that type of storm has a 1% chance of occurring each year. Similarly, what had been considered a 100-year event (10 inches of rain) was actually a 25-year event –– something with a 4% probability of happening in a given year.

The new rainfall data prompted the city to begin revising its floodplain maps five years ago.

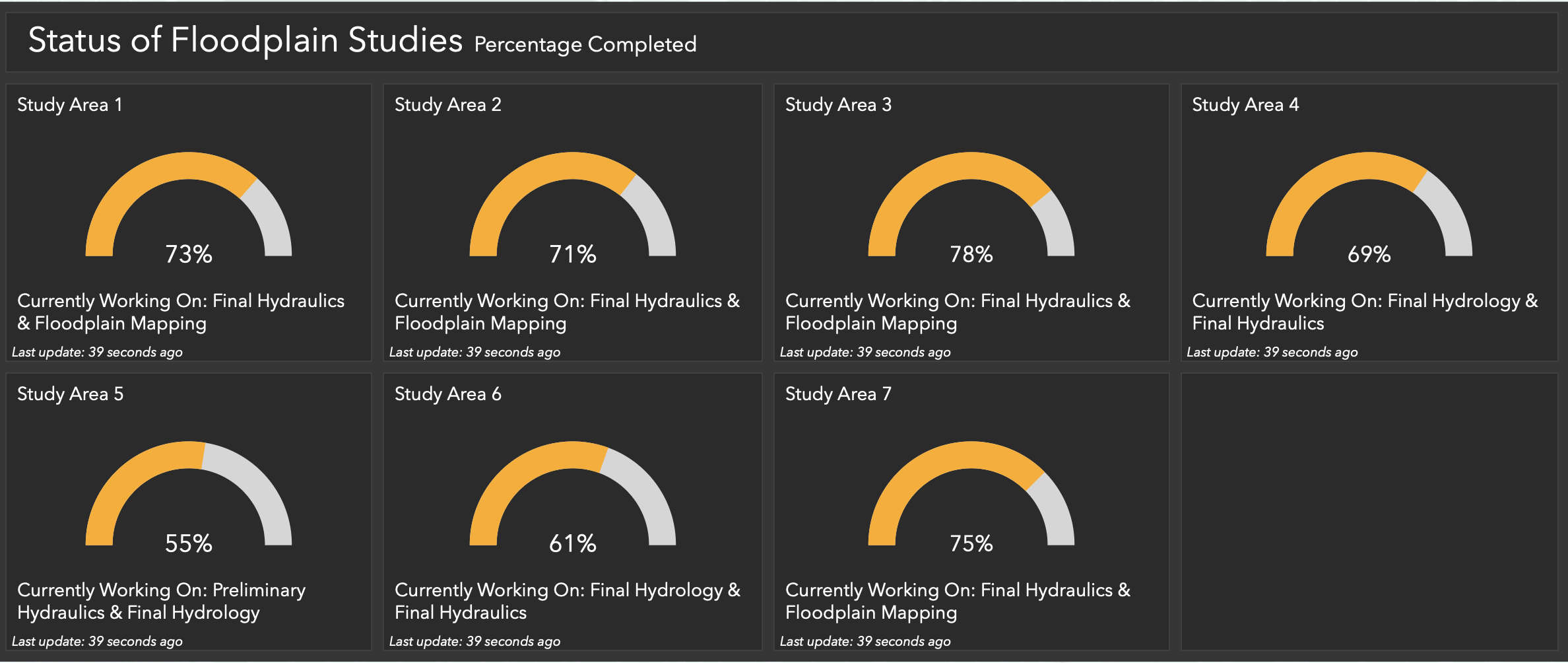

At this point, floodplain studies examining seven different areas of the city are between 55-78% complete, according to a public dashboard maintained by the Watershed Protection Department.

I have absolutely no frame of reference for how long these studies should take so I'm not in a position to judge if this is slower than usual. If you have any insight on the matter, please let me know!

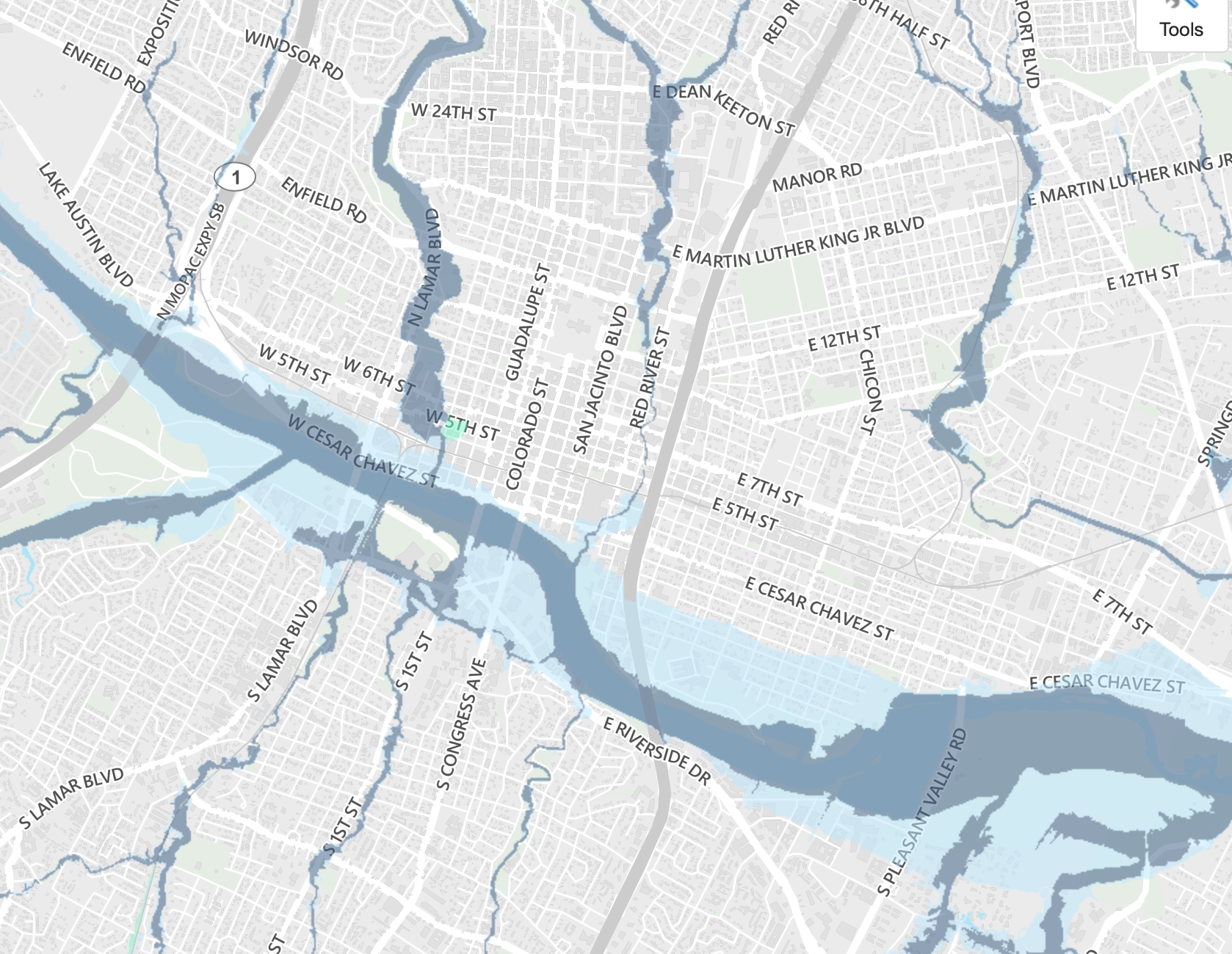

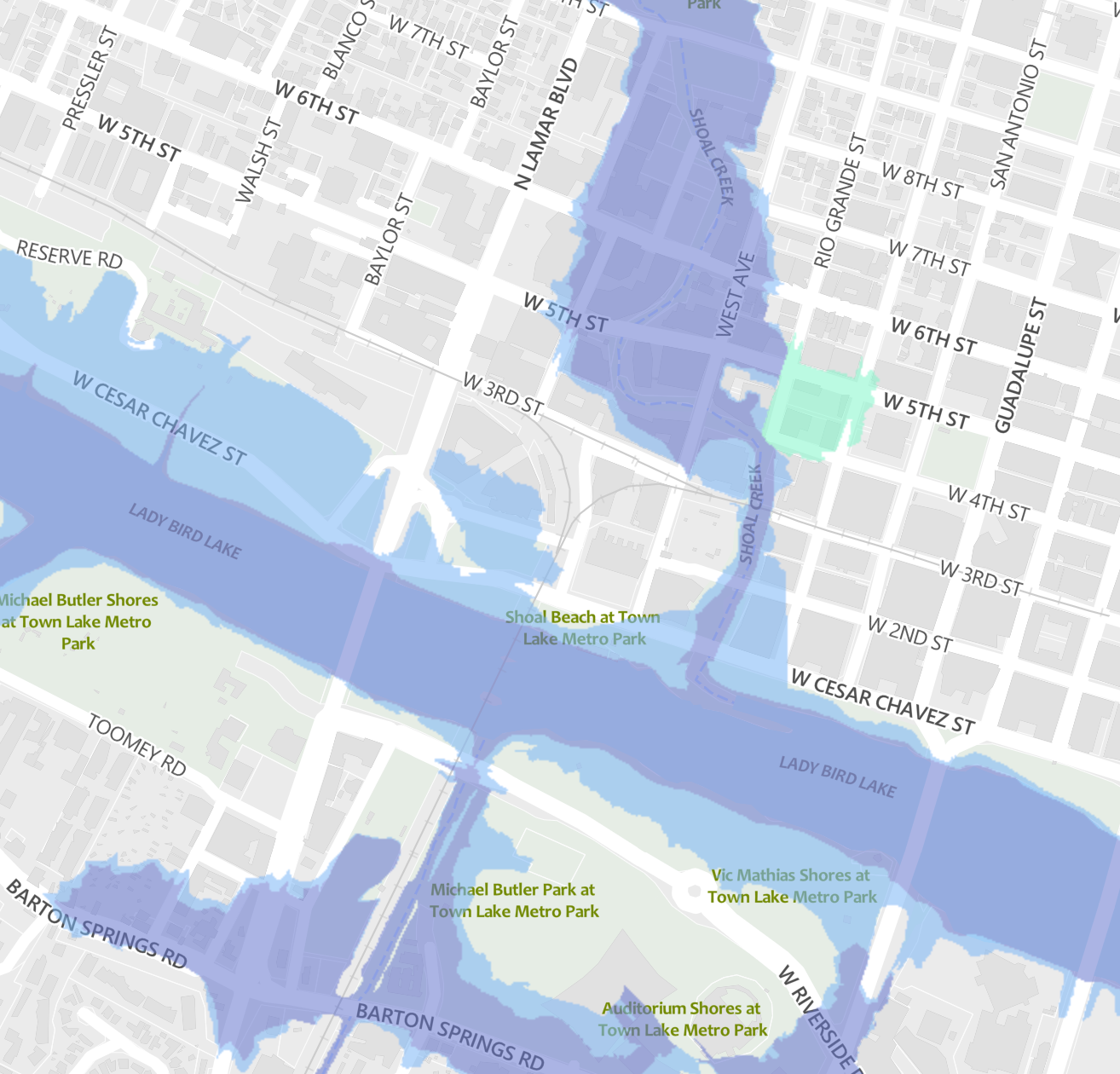

Because the city has not yet mapped the new 100-year floodplain, it has instead been relying on FEMA's 500-year floodplain. For most of the city's creeks, the difference between the two boundaries is barely perceptible on a map. The notable exception, however, is in neighborhoods near the Colorado River, including downtown and the east side, where the 500-year floodplain (light blue) extends far into residential and commercial areas.

Building in the floodplain

But the bottom line is that, as a result of Atlas 14, far more homes and businesses are considered in the floodplain than before, affecting what can be built and where. Development in the 100-year floodplain is subject to heightened requirements while development in the 25-year floodplain is completely prohibited.

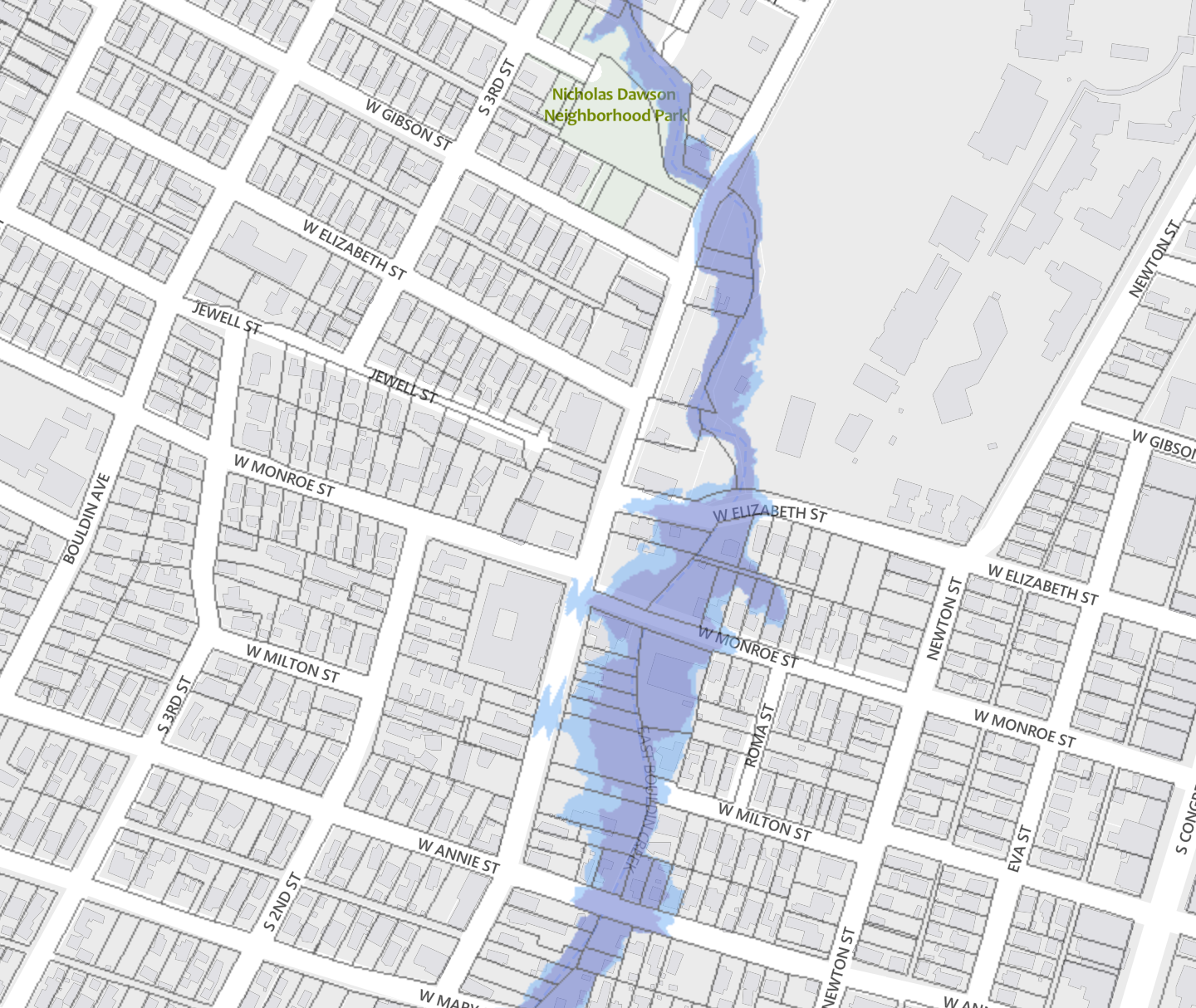

Since the city has not yet mapped its own 25-year floodplain, it is currently relying on its old 100-year fully developed floodplain, which estimates the amount of flooding in an area if it was developed to its full capacity according to existing zoning. Again, in many of the city's watersheds, there's not a big difference between the 25-year fully developed floodplain (purple) and the 100-year one (light blue). But the difference along West Bouldin Creek is certainly enough to affect some development along S. 1st St:

There's also a bigger difference along the river downtown (but not on the east side), but frankly a lot of this is already open space:

When it comes to flood mitigation, there has historically been a lot of focus on minimizing impervious cover: the part of the property that does not absorb water, like the building, the parking lot etc. This is why the threat of flooding is often a popular argument against upzonings or new development. But while a denser project may increase impervious cover on a given lot, in the grand scheme of things densifying reduces impervious cover citywide. If you want more green space, then it's better to build up instead of out.

Watershed experts have also consistently said it is possible for the city to densify without increasing flood risk. What is more important is that the city continues to build out its flood control infrastructure, both by investing in improved public drainage systems and by, in some cases, requiring developers to build obstacles to flooding, such as detention ponds. What types of development should trigger those requirements, however, is a long conversation for another day...

Ongoing investment in flood infrastructure

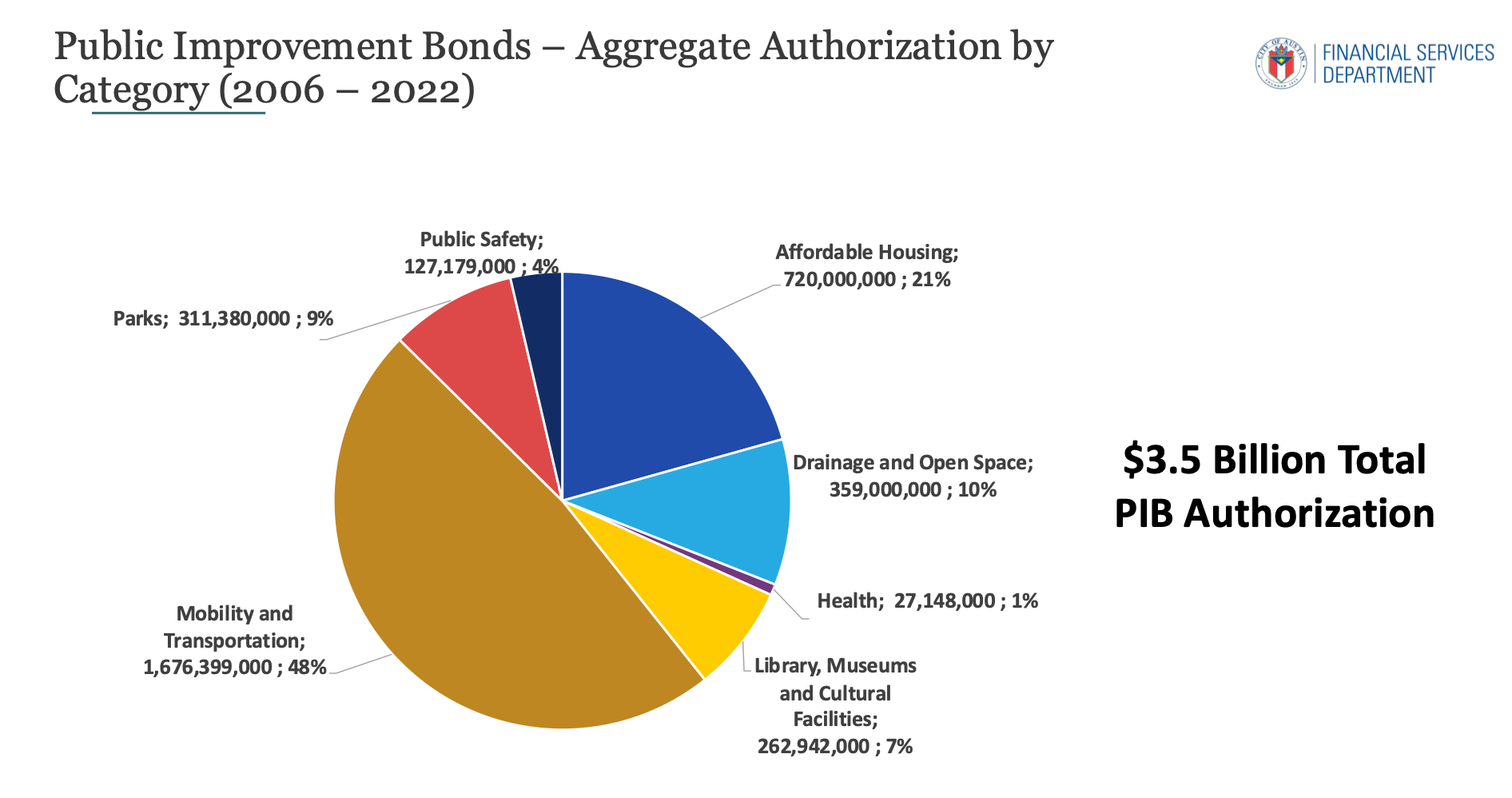

Since 2006, voters have approved $359 million for "drainage and open space," about 10% of the total bond funding approved during that period.

Just over half of that came in 2018. The signature bond issuance in that election was the $250M for affordable housing, but voters also approved a slew of other investments, including a $184M measure for flood control, open space and water quality preservation. Of that sum, $112M was for drainage projects, such as streambank stabilization, storm drains, low-water crossing improvements, and buying out property owners in flood-prone areas.

I don't have much insight on how that money is being deployed and what the city's future plans are to improve flood mitigation. I've sent a number of questions to the Watershed Protection Department and requested an interview with an expert in hopes of developing a better understanding. A spokesman for the department told me an interview likely wouldn't be possible this week but that he would work on getting answers to my questions in the coming days.

If this is your first time reading the Austin Politics Newsletter, you should know that it's published four times a week (Mon-Thurs)! Visit the website to sign up!