Some thoughts on Project Connect

Why does it cost so much?

Those who scorn public transit in general and rail in particular aren't the only ones upset about the way Project Connect has proceeded. Many transit supporters who were enthusiastic backers of the 2020 tax rate election that funded it have been deeply disappointed by how dramatically the first phase of the light rail routes has been pared back.

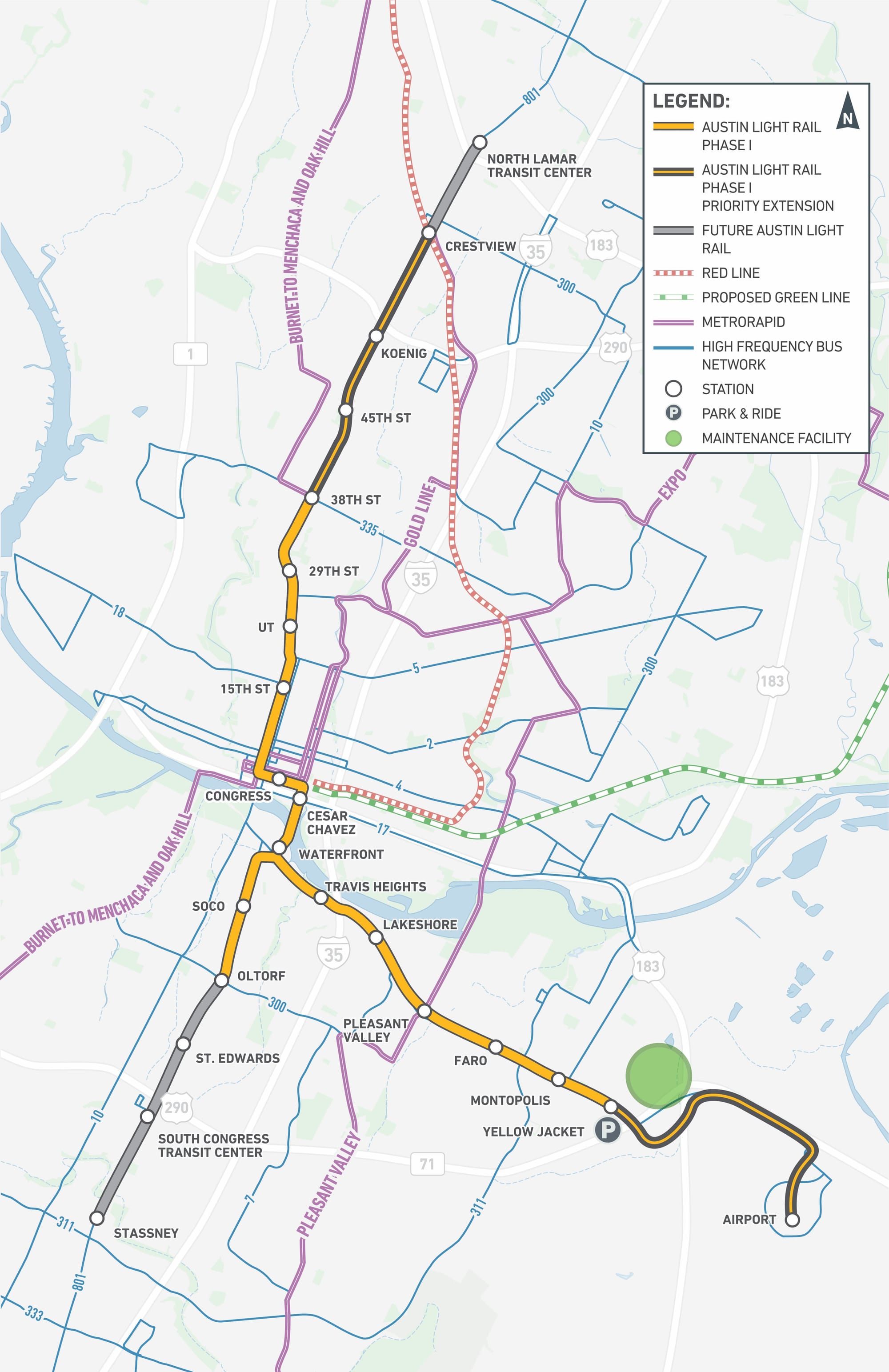

We thought we'd begin the 2030's with two long rail routes. The Orange Line would start at the North Lamar Transit Center at U.S. 183, run along Guad and through downtown, and then down S. Congress to Stassney Lane. The Blue Line would run from downtown, along E. Riverside, all the way to the airport.

The solid orange below shows the parts of the routes that are still planned for Phase 1. The "priority extensions," appears to be just a euphemism for "we hope they're coming soon afterwards!"

It's not just the length of the routes that has been a disappointment. The new plan also has the rail running at street level, rather than underground downtown, as originally proposed.

Some transit supporters see tunneling downtown as critical. They worry that a street-running train will run into frequent traffic delays due to downtown's many road intersections. They also worry that, perhaps decades from now, we won't be able to easily scale up the capacity of the train by adding more train cars, since doing so might extend the train beyond the (relatively short) block and into the intersection. Neither of these would be issues underground.

While people understand that every part of the transit-building process (labor, parts, real estate) has gotten much more expensive in recent years, they're also unnerved by how dramatically ATP has swung from pie-in-the-sky ambition in the first year following the vote, when the transit agency was talking about tunneling not only downtown but under much of S. Congress, to what feels like an almost religious devotion to "under-promise, overdeliver."

In the absence of the costly tunnel, many transit supporters are shocked that ATP is now projecting a per-mile cost of $500 million.

This tweet from national urbanist writer Matthew Yglesias was one among many to highlight the much-bemoaned efficiency gap between European transit systems and American ones.

€1.7 billion in Milan gets you 15 kilometers of tunnel vs $4.5 billion for 16 kilometers of surface transit in Austin pic.twitter.com/1iqojMgCuA

— Matthew Yglesias (@mattyglesias) May 23, 2023

This tweet from NY transit scholar Eric Goldwyn came from almost a year ago, when the number being thrown around was $450M per mile.

450M per mile of surface light rail is definitely a US record, at least based on this audit of projects from Minnesota: https://t.co/1dKAlfvARg pic.twitter.com/H6xqq24X7m

— eric goldwyn (@ericgoldwyn) May 23, 2023

Were our expectations too high or are we now settling for too little? Was it former Cap Metro CEO Randy Clarke who promised too much or is it current ATP executive director Greg Canally, a transit novice, who is selling us short?

In search of some of these answers I sat down recently with a couple of the top-level planners for the ATP: Jennifer Pyne, EVP of planning, community & federal programs, and Lindsay Wood, EVP of engineering & construction.

TL;DR: I'm still not quite sure what to think about where we're heading, but they offered me some important insights.

When it comes to cost, they pointed out that there aren't many recent starter rail projects in the U.S. to which we can compare. The most recent starters, as far as I can tell, were Norfolk (completed 2011), Phoenix (completed 2008) and Charlotte (2007).

Other recent rail projects in the U.S. have been extensions of existing systems, which tend to cost less. For instance, ATP is projecting the cost of the maintenance and storage facility, along with the vehicles themselves, at $1 billion, or about 20% of the capital cost.

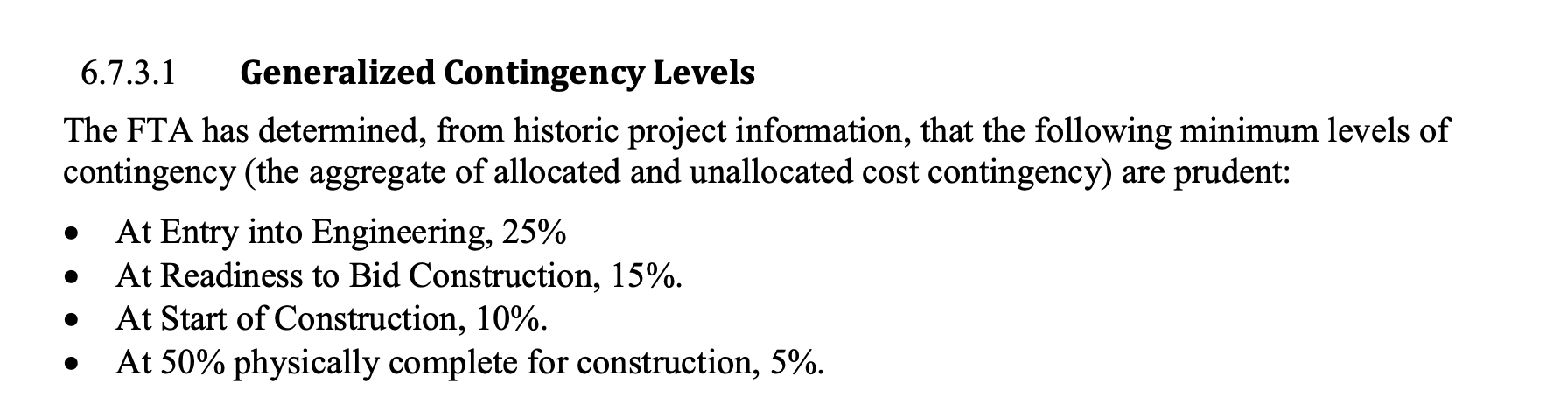

Moreover, ATP's proposed cost includes a whopping 40% contingency to account for unexpected costs. This FTA document from 2015 suggests that that is much higher than the historical average that the feds have demanded:

ATP officials have said that such a large contingency is not unusual among projects seeking federal grants these days due to the volatility in supply chain, labor and real estate markets in recent years.

There are growing pains involved with starting a system from scratch, but it's also a "great thing for us from a federal funding perspective," said Wood.

The assumption has always been that federal grants would account for around 45% of the cost, but there are hopes that the Federal Transit Administration, bolstered by an infusion of money from the 2021 infrastructure law and eager to support transit in one of America's largest and fastest-growing cities, will agree to chip in even more.

"I always say we’re targeting 50%," said Pyne.

Pyne, who oversaw big parts of the construction of Phoenix's light rail system, explained that the federal funding process is not as simple as submitting an application and getting a yes or no from Uncle Sam.

"We’re going to be submitting a series of materials over the years ... there are gates we have to go through. FTA is not going to let us proceed through those gates if they think we don’t have it together," she said.

Wood added: "We don’t anticipate any surprises at those checkpoints. You’re working collaboratively with the FTA the entire time."

Austin also faces some geographic and geometric challenges that some peer cities lack. Phoenix and Salt Lake City, which both built rail systems in this century, have laid the tracks in the middle of wide roads. They didn't need to acquire nearly as much real estate and the engineering wasn't nearly as complex.

For instance: the tough decisions about what to do on the Drag. Until a couple weeks ago, ATP said it would have to condemn a number of businesses, most notably burger joint Dirty Martin's. Now they've come up with different solution that will leave Dirty's in tact, albeit with (gasp!) only one access point to its parking lot.

But what makes this route difficult is also "what makes our project special," said Wood. The N. Lamar/Guad/SoCo route is the natural starting point for rail because it is the most vibrant. It has a high (albeit not high enough) mix of residential and employment density, lots of entertainment destinations and a high level of foot traffic. It is home to what is by far the most popular bus route (801).

This stands in contrast to the route championed by Cap Metro, former Lee Leffingwell and Austin's political establishment in the failed rail bond of 2014, which sought to run east of the university to Highland Mall. There wasn't nearly the population density and existing transit ridership, but it avoided some of the political and engineering headaches associated with Guad & SoCo. Of course, the 2014 vote lost in a landslide in part because many transit advocates, including a group founded specifically to advance rail, Austinites for Urban Rail Action, opposed it! They objected to the route and the uncertain financing mechanism, which risked putting the rest of the transit system in financial jeopardy.

And thus is the irony of our current predicament. Project Connect was exactly what the transit wonks wanted: the right route and a permanent funding stream. And yet the project's virtues are what its opponents are seizing on to try to defeat it.

Hence the lawsuit claiming that instead of getting voters to simply approve a tax, ATP must get voters to approve a bond, which would be far less fiscally prudent. Hence the bitching and moaning about pedestrianizing the Drag.

It's too bad that the criticism of ATP and Project Connect that gets the most attention in local media comes from a small group of grouchy old reactionaries who know and care nothing about non-car transportation.

And yet, the sad truth is, the same conservative curmudgeons who have become irrelevant in local politics still carry weight among the mouth-breathing majority at the Capitol. So in a way, their ill-informed bitching is more politically relevant than the informed critiques from transit experts.

It's a sad state of affairs.