How much time do we need?

What is the right amount of public comment?

Two Travis County judges have now sided with Save Our Springs Bill Bunch in his lawsuit against the mayor and City Council for limiting his speaking time at a recent Council meeting.

Throughout most of my time covering City Council, the norm has been that people who wanted to speak on an item were given three minutes to speak. Since Watson came into office, however, the limit has generally been two minutes. I frankly didn't even notice that the speaking times had gotten shorter, and I hadn't heard anybody object to it.

The lawsuit was prompted by a meeting on April 4, when Bunch signed up to speak on four items before Council. All of his items were on the "consent agenda," meaning nobody on Council had "pulled" them for debate. These are the uncontroversial items that are passed all at once at the beginning of the meeting.

Bunch believed that he should have two minutes to speak on each item, or eight minutes total. But he was cut off after two minutes, much of which had tragically been consumed by his argument with the mayor about how much time he should have.

Neither the city charter or state law specify how much time a person should get to speak on a matter before Council; they only say that people be given "reasonable" opportunity. Nevertheless, the temporary restraining order issued by Judge Madeleine Connor two weeks ago required Council to give people three minutes on each item.

This raised the terrifying prospect of Bunch or another one of the city's public input enthusiasts signing up for dozens of items and spending upwards of an hour addressing Council. Mercifully, however, GAVA's Monica Guzman, who signed up for 13 items at the first meeting after the ruling, ended up consuming less than two minutes of the 39 to which she was entitled. She was one of the three witnesses Bunch called at trial to make the case for more speaking time.

Yesterday another judge extended the restraining order for two weeks and noted that the city is required to pass an ordinance specifying the speaking rules. For a number of years now, under both Adler and Watson, the rules have been fluid, typically set at the discretion of the person chairing the meeting, which is usually the mayor.

Both mayors have occasionally limited speaking time to one minute per person if there is a particularly large crowd waiting to speak. Adler often faced pushback from the anti-growth bloc for limiting speaking time, particularly on contentious zoning cases, but the others on Council typically sided with him.

Kathie Tovo, the former Council member and current mayoral candidate, said she was "very, very reluctant" to reduce a speaker's time, especially given that the speakers had often planned a three-minute address.

"They prepare for that three-minute period and it really throws their preparation into chaos," said Tovo.

Others reason that cutting down on each speaker's time also cuts down on the time people spend waiting to speak. That allows more people to participate.

There has always been debate about when Council should take up certain business. Tovo, for instance, said that she believed that Council should try to take up big items (or those that have generated a lot of public interest) in the evening, when the most people will be able to attend.

Tovo said she is very disappointed with how Council has handled meetings since Watson has come into office.

"This Council needs to do a better job of putting items that people want to participate in after work hours," she said.

In the good old days it was common for people to "donate" their time to another speaker. A group of neighbors would all give their time to a designated spokesperson, who would use it to give a lengthy presentation. That practice was also curtailed (but not abolished) during the Adler years.

During the pandemic, when the meetings were remote, Council began allowing people to speak on any item –– consent or pulled –– at the beginning of the meeting, rather than requiring people to wait for Council to take up the item. That practice has persisted.

What is a reasonable amount of time?

There's no easy answer to this question. But whatever amount of time Council settles on, I don't see how they can decide to essentially reduce the limit for someone who signs up to speak on numerous items. Bill Bunch has a point!

The funny thing about this debate is that there are really only a few people who might go through the trouble of speaking on numerous items. The most likely suspects aren't even hardcore activists, most of whom understand there are more effective ways to communicate with their elected officials. The bigger threat to Council's time and patience probably comes from the handful of wackos and performance artists who show up for every meeting to mutter nonsense into the microphone. And I'm actually not including Bunch in that group.

I suppose it could be an interesting pressure tactic for activists to use. Just imagine: a handful of advocates sign up to speak on every item, forcing City Council members to sit silently as the activists drone on about issues that they don't actually care about –– concrete contracts, random zoning cases, board appointments –– just to waste their time. It might work, or it might backfire horribly.

But that would be an extraordinary event: there aren't that many people with the dedication to pull it off.

Does speaking to Council actually work?

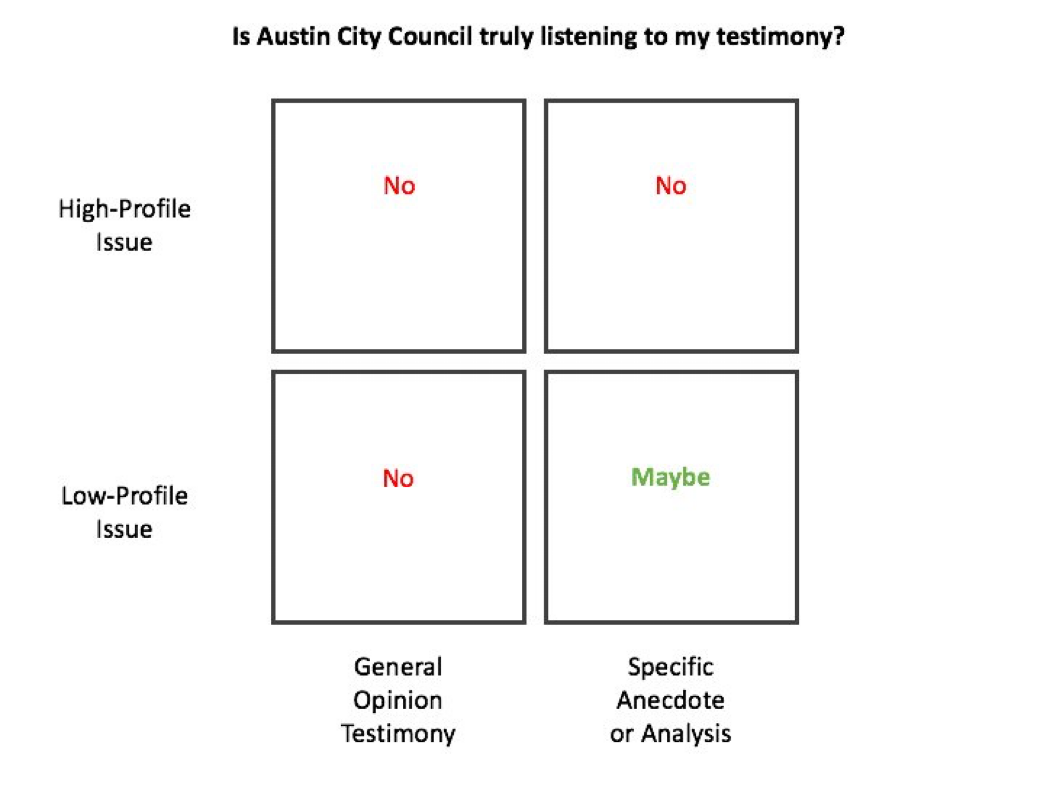

A few years ago Julio Gonzalez Altamirano tweeted the following theory of public testimony:

He distinguishes "truly listening" from what happens on high-profile issues, which is that Council members are influenced by the number of people who show up to speak on an item, even if they're not going to closely listen to what each person says.

If somebody forwarded you this email, please consider subscribing to the newsletter by visiting the website.